THE NUMBERS GAME

Decoding cast-iron numbers.

What’s in a number? It’s a question commonly asked when it comes to cast iron. Look on the bottom or handle of many an antique pan and you’re likely to find 6s, 8s, 10s, and so on, as for decades, numbers were signature features on these skillets. So much so that new pan companies have started to numerically mark their own, paying tribute to the old practice. Which is one, it turns out, as useless today as our tiny cast-iron Alma. (Though no offence to either.)

The answer to our original question is shrouded in its fair share of myth and controversy, but we do know that its origins date back just over two centuries, when the Age of Enlightenment would bring about many a pivotal innovation and invention, especially in relation to our kitchens.

For our purposes, perhaps the most important development arrived on the eve of the 1800s, with the process of standardization. We used measurements back in those days, but throughout the 1700s, we still had yet to figure out to make life easier by developing some set of standards, aka models with which to compare things. Even as we created the influential likes of the lightning rod, the piano, the smallpox vaccination, we never made two nails—let alone two skillets—that were exactly the same.

Enter standardization, which arose out of the Industrial Revolution, when standards were invented and implemented to both improve and increase production. Many say it all started with Eli Whitney, the New England inventor of the cotton gin, who in 1797 proposed the making of flint-powered firearms with interchangeable parts. Up until that moment, each gun was made one by one, piece by piece, bit by bit, by the hands of a single gunsmith. But credit is also due across the pond to two Englishmen, Marc Brunel and Henry Maudslay, who at the same time were crafting identical pulleys and precision tools for shipbuilding, as well as an early production line.

With the invention of identical, interchangeable parts, manufacturers were now able to start making larger runs of the same item for the very first time. Standardization enhanced product uniformity and drove down price for the customer. And as manufacturing advanced, so, in many cases, did the standard of living.

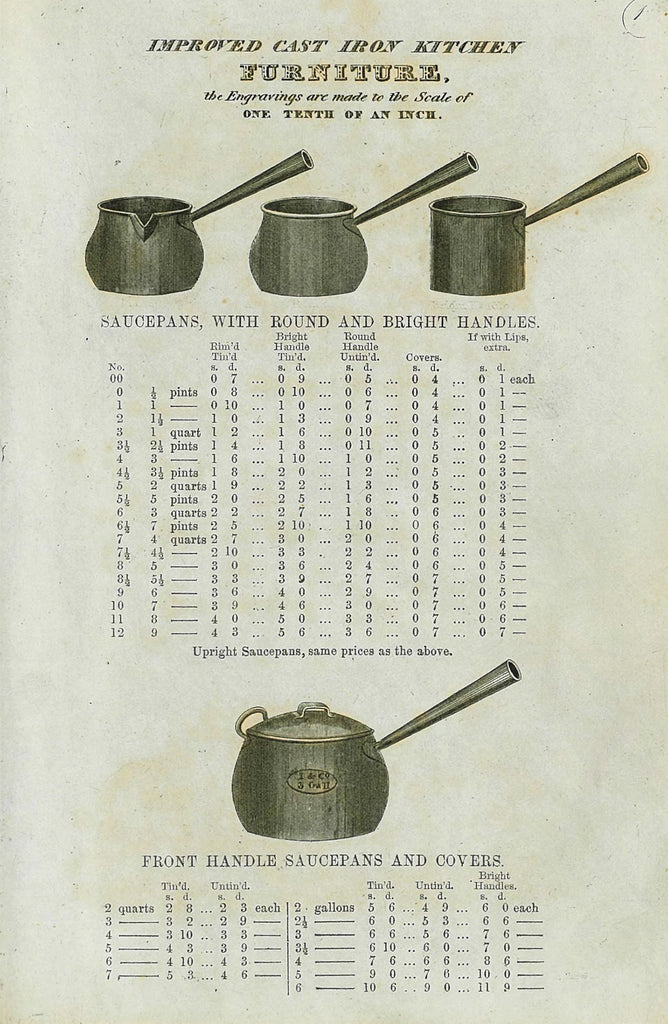

Exhibit A is the early cookstove, invented in the first half of the 1800s. A dramatic upgrade from open hearths in terms of cleanliness and safety, these enclosed stoves, eventually made out of cast iron, began to be produced en masse and quickly became a fixture for middle-class homes. Before long, iron foundries realized they had found a gold mine, and began making cast-iron cookware as an easy add-on.

Contrary to popular belief, these numbers did not usually equate to exact or even actual measurements, such as the diameter of the eye or pan, as proven by the Favorite 1, or better yet, the Griswold 0. On top of that, a Lodge 10 was not the same as the 10 of a Wagner, or any of the other guys, with standardization existing within brand but missing the industry-wide memo.

Today, just to make matters even more confusing, we’ve decided to use letters. Where our handle’s base meets our pan’s rounded edge, you’ll find a small loopy squiggle—in fact, an initial—with each pan named in honor of someone who has influenced us in some seminal way. They are mothers, wives, grandmothers, great aunts, and increasingly, fathers, uncles, cousins, sons. And a few pals of Butter Pat thrown in for good measure.

We figured that, since the numbers are antiquated with our modern stoves anyways, we might as well use a design element that means something, if only just to us. And that tells a story, if only one just slightly less complicated.

They are in indeed an homage to the past—to the tradition of numbering cast irons, to all of the practice’s legend and lore. But at the core, these letters, literally hand-drawn by our founder and located at the grip of our own fingertips, are meant to remind us.

About the people who make these pans. About the former foundrymen who also inscribed early cast irons, using a simple stylus to carve those numbers right into the pattern’s clay. About Estee and Heather, Joan and Lili. Our friends Eric and Joe. Even little old Aunt Alma.

That they were here, and we were, too, before the measurements or mass production or machines took over. And hopefully will be long after.

We didn’t realize in the beginning, but with these names, the pans themselves have become personified. It’s an unintended consequence but welcome embodiment—through the meals they make and the community they create in the kitchen or around the table—of what makes us human.

Which, of course, is anything but standard.