THE HOLIDAY HAM

A hyperlocal delicacy, Southern Maryland stuffed ham is the stuff of legends.

Dear readers, as many of you now well know, we are more often than not writing to you from our home on the Chesapeake Bay, situated on the tidewater edge of Maryland, also known as the Old Line State.

We’re a small-but-mighty terrain divided by our nation’s largest estuary, with its sprawling watershed cultivating a multitude of distinct communities—and in turn traditions—from river to river, sometimes stream to stream, even creek to creek.

To the east, in our neck of the woods, is the Eastern Shore, a low-lying landscape rooted in its farm fields and brackish tributaries, from which so much of our state’s iconic sweet corn, summer tomatoes, blue crabs, and oysters often hails. And to the west, we have our big cities—Annapolis, Baltimore, and onwards into Washington, D.C.

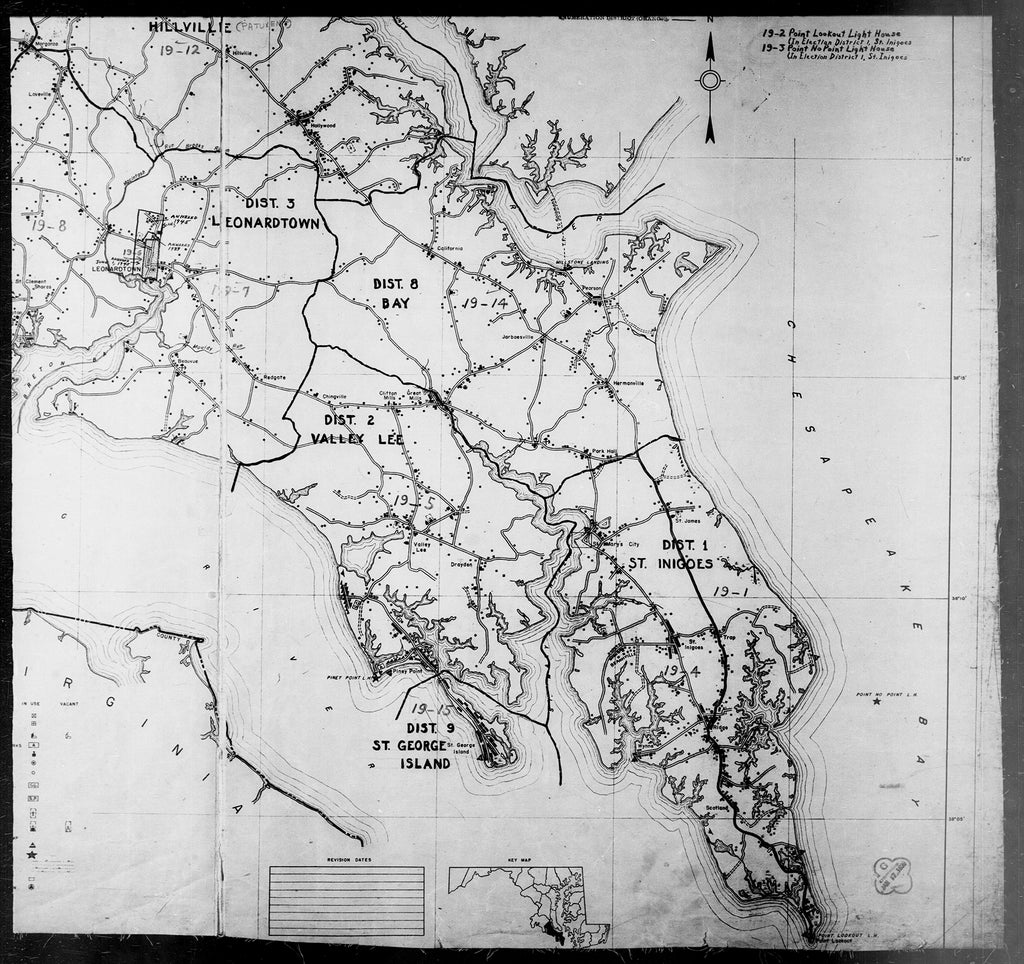

A map of St. Mary’s County.

But more importantly still (for our purposes here today), to the south, there is a wide, craggy peninsula that leads down the Western Shore—miles and miles and miles, past suburbs, onto country two-lanes, through thickets of pine forest, never far from sandy cliffs, into another sense of place and time that bottoms out at the mighty Potomac, just north of the Virginia line.

And it is here, and only here, in the deep heart of Southern Maryland—some 70 miles south of the state capital—and in St. Mary’s County, more specifically, that you can find the delightful hyper-regional delicacy that we’ve come here to tell you about today: stuffed ham.

“Stuffed ham?!” we expect you to ask incredulously. We once had the same reaction, too.

We can’t recall when we first learned about this peculiar pork dish. Maybe it was that Church Lady in our old stomping grounds of Alexandria, Virginia, who grew up down that way and brought us back our first taste in the 1990s. Or maybe it was Mrs. Edward Edelen’s recipe appearing the iconic local cookbook, Maryland’s Way. But whenever it was that we discovered it, the obsession—not unlike the West Virginia hot dog—was instantaneous. We had to know, and eat, more.

After all, “Occasionally one hears of a newcomer—a visitor, even—whose sensitive palate quivers with delight at the first piquant bite,” wrote The New York Times in 1982, with what has been heralded as one of America’s most hyper-regional dishes never expanding beyond its native range.

Hearty greens to stuff the ham.

In the close-knit communities of St. Mary’s County, stuffed ham is a source of great pride. Each family has their own recipe, often perfected over multiple generations. There are subtle differences between each, and all could start a decent argument. Kale or cabbage. Red or black pepper. Mustard or celery seed. Both. Neither. All of the above. Whatever the preference, it is the definition of a labor of love—and not for the impatient.

For starters, you always begin with a whole fresh ham—though great debate still ensues over whether to debone or not to debone. It is corned, aka cured in salt or brine, then generously sliced with deep slits, before being stuffed and smothered with several pounds of a well-macerated mixture of hearty greens. Turnip tops and watercress are thrown in occasionally, plus a hefty dose of alliums, seasonings, and spices to the maker’s liking.

From there, the ham gets unceremoniously swaddled in whatever fabric you can sacrifice to the swine gods—cheesecloth, pillowcases, even an old T-shirt—before being dropped into a big pot and boiled for several hours. Once it reaches a desired temperature, it is cooled quickly, wherever it might fit: in a fridge, in an extra-large cooler, on a below-freezing back porch.

Boiling a ham.

The whole process takes a couple days, but when it’s all said and done, the stuffed ham is sliced cold and served on a sandwich or by its lonesome. Condiments are a point of contention.

“It’s quite an undertaking,” says Kara Mae Harris, a Baltimore historian behind the regionally beloved food blog, Old Line Plate, who has spent the last decade following the unofficial Stuffed Ham Trail of Southern Maryland in search of this elusive deliciousness.

No one knows the stuffed ham’s exact origins, which likely date as far back as the 1600s.

By now, though, most agree that the dish has roots in Afro-Caribbean culture, likely cultivated by the local enslaved population of this deeply entrenched tobacco-growing region and passed on by word-of-mouth. Multiple iterations appear in 300 Years of Black Cooking in St. Mary’s County, an esteemed community cookbook, in which African-American descendants recall their ancestors’ ingenuity in combining pork scraps with garden-grown greens to create a comfort food that could last the ages. Eventually, stuffed ham made its way to the head table, and it has remained a ritual shared between both Black and white households ever since.

Drying tobacco in St. Mary’s County.

These days, the real deal is still made for special occasions, be it a county-fair cook-off, seasonal church fundraiser, or a family’s holiday feast—especially on Easter, when “the air in St. Mary’s County is permeated by the odor of stuffed ham a-cooking,” wrote The Baltimore Sun in 1950. Though it appears at Thanksgiving, and Christmas, and just because, too.

And if you’re lucky, you can still find it like Harris has—at country stores, small supermarkets, or the sporadic gas station, sold as a sandwich or even whipped in egg rolls or thrown on top of pizza—with its charcuterie-like salty-sweet, slightly spicy, punchy piquant flavor making it a one-of-a-kind accoutrement. Those places are becoming harder and harder to come by, being lost to changing communities and traditions and tastes, like so many of our most authentic foodways.

A stuffed ham, illustrated by Ben Claassen, courtesy of Old Line Plate.

“I’ve struggled to describe why it’s so good, and the answer is, I don’t know,” says Harris, who adds chile de árbol to her personal version. “It’s that devotion, and the difficulty, and the specificity that makes it so special. And when done right, it comes out so succulent, with those savory greens, then you put it on some bread with a little mayonnaise, and it's like no ham salad you’ve ever eaten.”

Simple alchemy, perhaps?

“Exactly,” says Harris. “It is really so much more than the sum of its parts.”